Probiotics: How to Choose the Best One For You

Including 22 of the Most Common Species

Author:

Amanda Ledwith, BHSc Naturopathy

Last Updated:

22 Jan 2026

Reading Time:

29 mins

Categories:

Probiotics & Bacteria

probiotics

What You'll Learn

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when taken in adequate amounts, provide measurable health benefits. However, choosing the right probiotic requires understanding your unique gut microbiome—what works for one person may not work for another, and inappropriate supplementation can sometimes slow healing rather than accelerate it.

The most common probiotic bacteria come from the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium groups, each offering different benefits depending on the species and strain. Before supplementing, testing your baseline microbiome levels provides essential data for targeted, effective probiotic selection.

This guide covers the 22 most common probiotic species, their specific benefits, and how to choose the right approach for your situation.

What Are Probiotics?

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) defines probiotics as:

"Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host."

The ISAPP further explains that only strains which have been scientifically proven to have positive health effects should be named a 'probiotic'. In a strict sense, the live microorganisms found in fermented foods and beverages aren't typically classified as 'probiotics'—though science often catches up with traditional wisdom.

Probiotic supplements often contain many different microorganisms. The most common probiotic bacteria come from the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium groups. Other types include the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii and Bacillus coagulans—each offering different benefits.

Understanding Probiotic Nomenclature

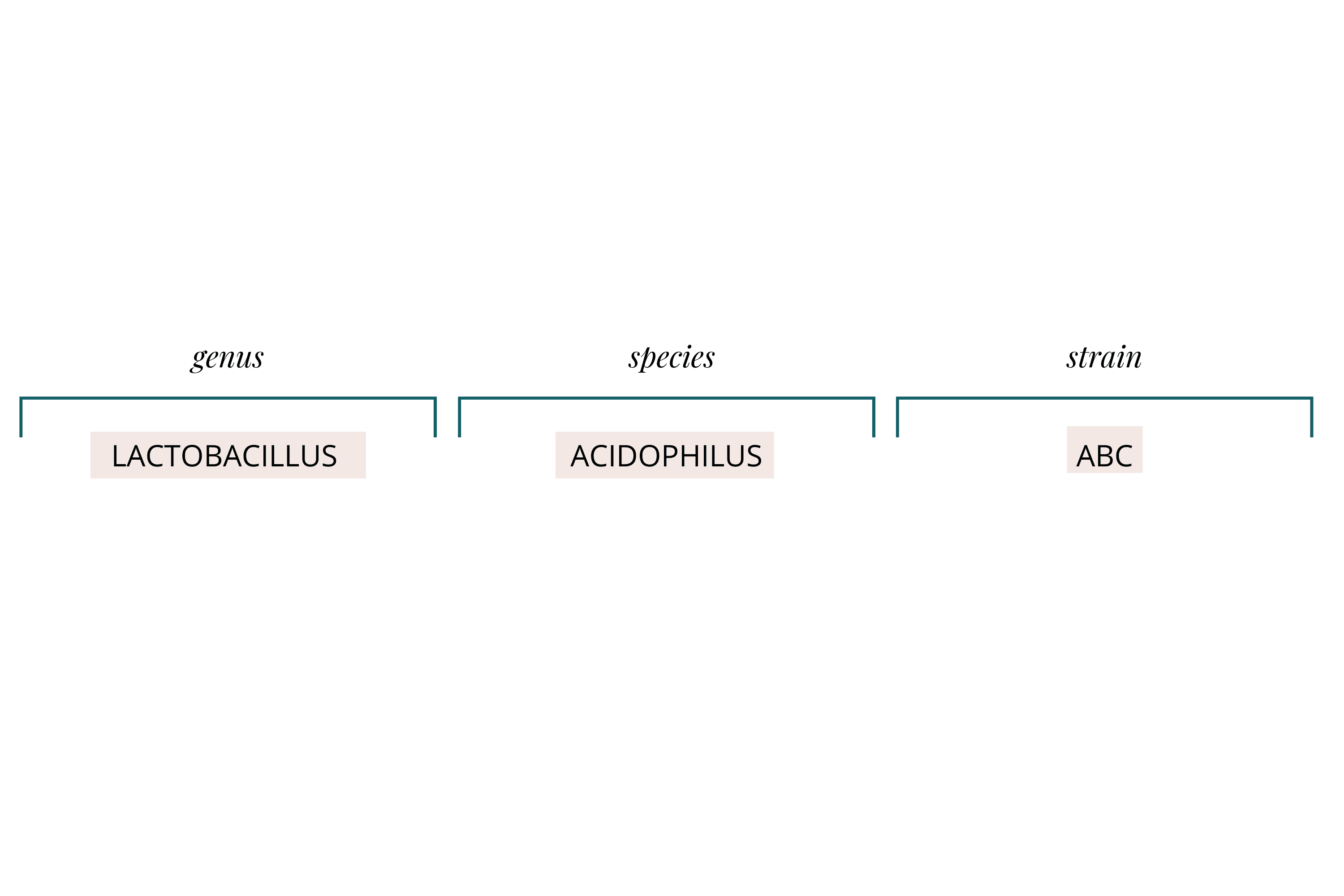

Different probiotics offer different benefits, and you'll find them listed by their scientific names: a genus, species, and strain.

For example, Lactobacillus acidophilus ABC breaks down as follows:

Genus (e.g., Lactobacillus): Functions like a surname, grouping genetically and biochemically similar species under an umbrella

Species (e.g., acidophilus): Further groupings with similar characteristics

Strain (e.g., ABC): Specific groups within a species—different strains within the same species can have different health effects and may even prefer different prebiotics

Prebiotics, Probiotics, Postbiotics, and Synbiotics: What's the Difference?

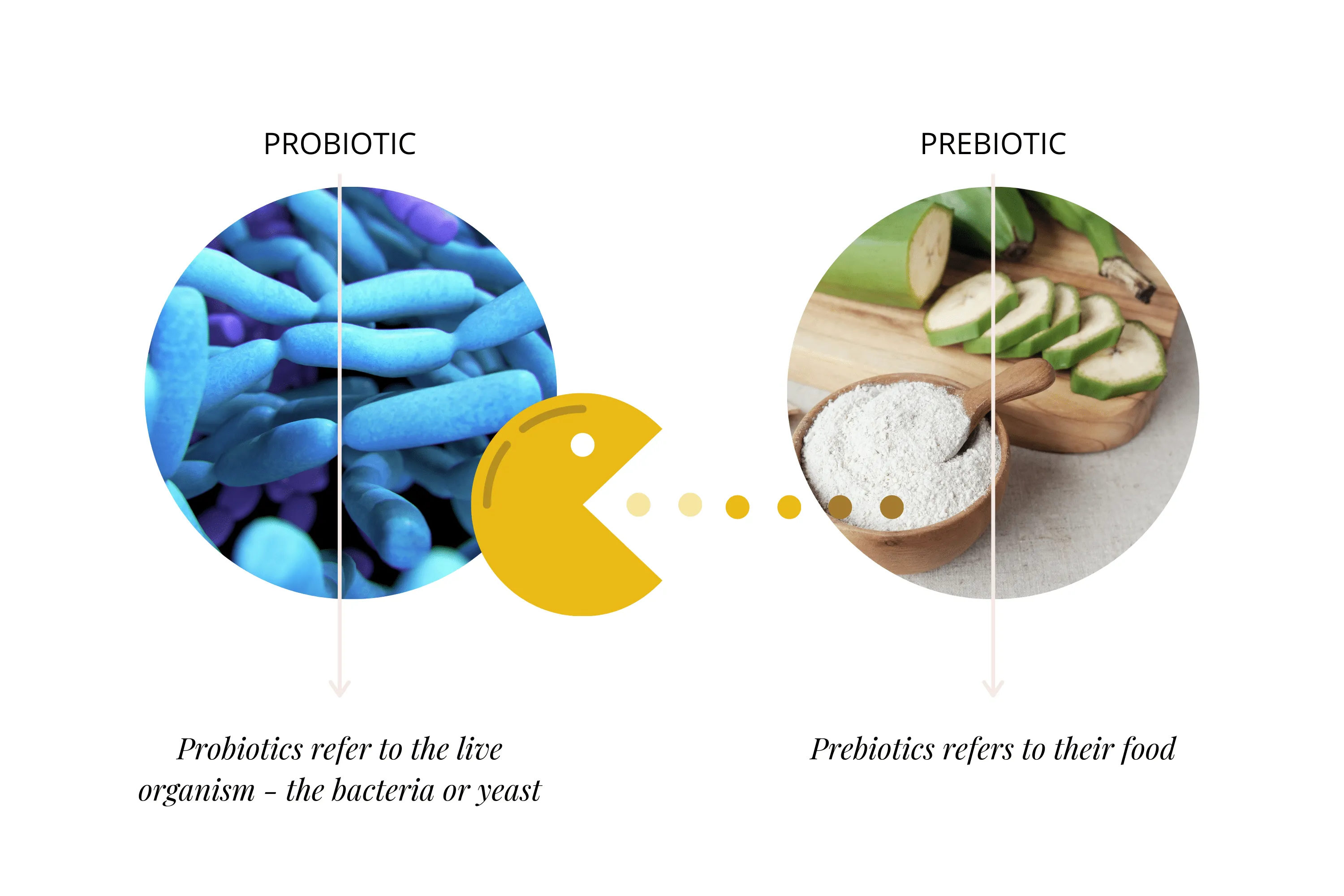

Probiotics refer to the live organisms—bacteria or yeast—while prebiotics refer to their food. Think of "pre-" meaning before: food comes first, which feeds the bacteria and allows them to multiply.

We cover prebiotics in depth in our prebiotic article. In brief, prebiotics are specific food components (often complex carbohydrates) that resist human digestive processes and end up in the lower intestines intact. Here they provide energy for beneficial bacteria—our resident probiotics. Their beneficial by-products, like renowned short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), are called postbiotics.

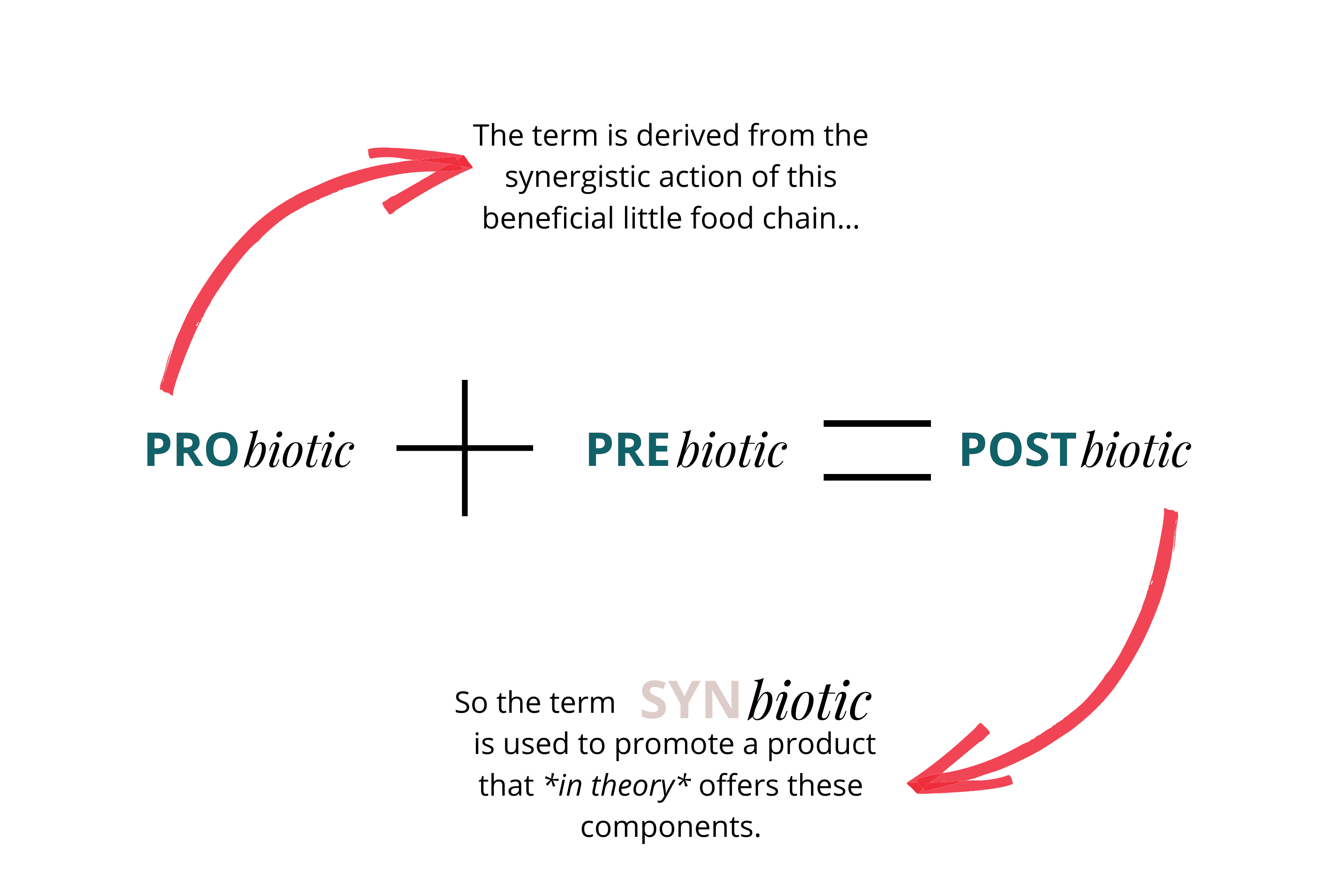

Synbiotics were described in 2011 and refer to products containing "a mixture of live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilised by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host." In essence, synbiotics are mixtures that include a specific prebiotic to feed the probiotics in the formulation, which then produce postbiotics.

The term derives from the synergistic action of this beneficial chain:

Prebiotics + Probiotics → Postbiotics

How Do Probiotics Work?

While there is substantial research on probiotics, it's important to note that there is currently no way to precisely trace the mechanism of action of prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics as they happen in real time inside the body.

Additionally, because the community dynamics within your gut are extremely complex and absolutely unique, what may work for you may not have the same effect on someone else. Your microbiome is a unique fingerprint.

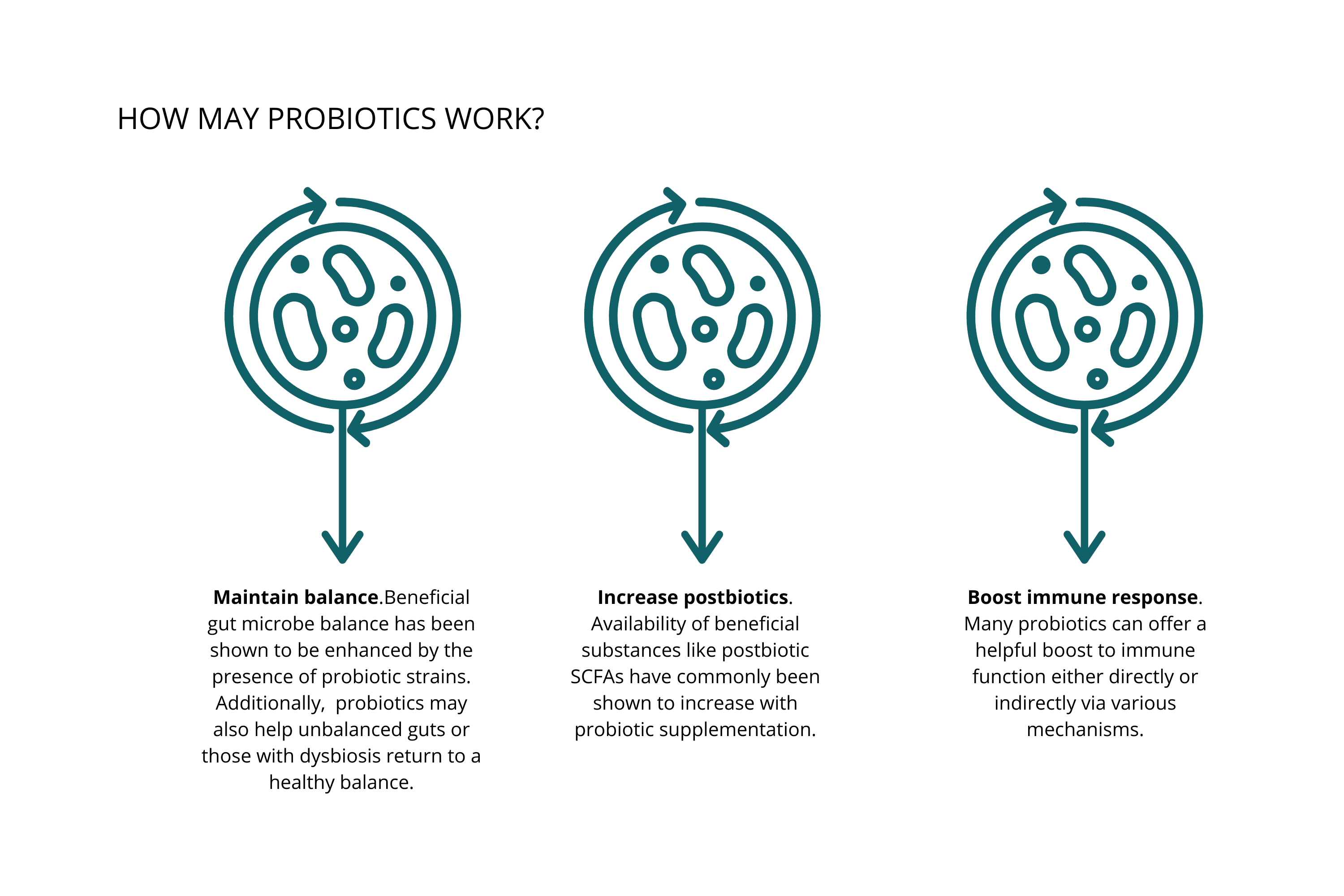

In general, probiotics may:

Maintain balance. Beneficial gut microbe balance has been shown to be enhanced by the presence of probiotic strains. Probiotics may also help unbalanced guts or those with dysbiosis return to a healthy balance.

Increase postbiotics. Availability of beneficial substances like postbiotic SCFAs has commonly been shown to increase with probiotic supplementation.

Boost immune response. Many probiotics can offer a helpful boost to immune function either directly or indirectly via various mechanisms.

These effects are broad-stroke benefits—specific benefits vary between species and even between strains of the same species.

Which Conditions May Benefit from Probiotic Use?

Despite the substantial volume of research on probiotics, there is still much to learn about safety and efficacy with specific conditions.

The most studied conditions with probiotic use include:

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

Prevention of NEC (necrotising enterocolitis) and sepsis in premature babies

Infant colic

Periodontal disease

Ulcerative colitis

Even within these study areas, researchers often point out the need for further research—specifically regarding probiotic levels of benefit, interactions, and optimal timing.

The order, timing, and dosage of supplementation matters. I've seen this firsthand with countless clients. In some cases, healing can be slowed by incorrect supplementation of probiotics, just as it can be enhanced in other cases.

Can Probiotics Be Harmful?

This brings us to an important consideration: the need to address gut lining health BEFORE supplementing with some strong probiotics—and the value of working with an experienced and qualified health practitioner.

While the science may indicate a particular strain is effective against certain conditions in the lab or in specific patient groups, first-hand clinical observations of thousands of clients and their microbiome profiles provides experience and knowledge that cannot be captured in a single study.

Although probiotics have an extensive history of apparently safe use—particularly in healthy people—very few studies have looked at safety in the detail needed. There's a lack of solid information surrounding side effects, and these effects are thought to be greater in those with severe illness and reduced immune systems.

As with any supplement, both the benefits and risks should be considered. This is why working with a health professional who can test your baseline levels, monitor your symptoms, and reevaluate if needed is so important.

Potential Side Effects of Probiotics

Some possible harmful effects of probiotics (usually in compromised individuals) include:

Infections

Production of non-beneficial by-products

Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes

Contamination with microorganisms not listed on the label and missing strains are additional risks, especially in lower-quality products. This is why practitioner-grade supplements are essential.

Another important consideration is the production of D-lactate by some probiotic species—a condition called D-lactic acidosis has prompted investigation. There are claims that excess D-lactate is linked to chronic health conditions like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and associated oxidative stress.

While the scientific community doesn't yet agree whether this is a common concern, many common probiotic species are D-lactate producers, including Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and E.coli.

🔬 VICTORIA'S EXPERT INSIGHT

"When I review microbiome test results, I often see clients who have been supplementing with probiotics for months—sometimes years—without testing first. What's concerning is that many have created imbalances by over-supplementing with strains they didn't actually need. I've seen Lactobacillus levels that are far too high relative to other beneficial bacteria, which can create its own set of problems. The key insight here is that 'more probiotics' doesn't equal 'better gut health.' Your microbiome needs balance, and the only way to know what your gut actually needs is to test first, then supplement strategically."

— Victoria, Microbiologist

Book Your Free Evaluation Call

How Do I Choose the Best Probiotic Supplement?

Our primary recommendation: find a practitioner who tests first.

Many of our clients have supplemented with probiotics before coming to see us. Often, they have a thriving community of a particular strain—sometimes in excess and without balance. Understanding what you start with allows you to build your gut microbiome back to health systematically.

That said, if you are generally healthy without underlying gut health concerns and have determined that a probiotic could benefit you, look for a high-quality, multistrain supplement that includes these 8 key species:

L. acidophilus

L. reuteri

L. rhamnosus

B. animalis

B. bifidum

B. breve

B. infantis

B. longum

The 22 Most Common Probiotic Species

The Lactobacilli

Lactobacillus are one of the bacterial groups that make up the Firmicutes phylum, which comprises the largest portion of our microbiome—roughly 50 to 70%. They are also a major part of the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) group, which includes Lactococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and others.

These bacteria convert sugars to lactic acid, producing an acidic environment that hinders the growth of several harmful or pathogenic bacterial types.

Lactobacilli make excellent probiotics because they:

Are tolerant to bile, acid, and gastric juice

Can adhere to the intestinal lining

Resist antibiotics

Produce beneficial EPS (exopolysaccharide sugar compounds) — e.g., L. plantarum EPS has antioxidant, antibiofilm, and antitumor actions

Remove cholesterol

Lactobacillus along with Bifidobacterium are the first live bacteria to colonise the infant gut during natural delivery.

One consideration that isn't widely discussed is the temporary (transient) nature of most lactobacilli. They don't form stable colonies in the gut and often disappear a few days after supplementation. This indicates that short-term daily probiotic intake is insufficient to correct gut probiotic levels—confirming that gut healing is a marathon, not a sprint.

1. Lactobacillus acidophilus

L. acidophilus is one of the best-known probiotics, largely due to its common addition to commercial yoghurts. Native to the vaginal microbiota along with many other species, L. acidophilus is also frequently included in probiotic supplements.

L. acidophilus has been shown to:

Actively inhibit growth of the yeast Candida albicans and help reduce biofilm formation

Stimulate electrolyte balance mechanisms in the gut lining, inhibiting diarrhoea

2. Lactobacillus plantarum

L. plantarum has recently undergone a name change and been officially reclassified as Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum, though the established name remains in common use.

L. plantarum are thought to be the most flexible and adaptable lactobacilli to stressors, with a unique and large gene sequence that researchers believe contributes to its resilience. This species can be found in saliva, the human gut, dairy products, vegetables, meat, fish, and silage.

Gut-specific properties of L. plantarum include:

Preventing endotoxin production in the gut—toxins associated with dysbiosis, liver inflammation, and other issues

Reducing intestinal permeability by maintaining tight junction integrity between gut cells

3. Lactobacillus casei

You may have heard of the Shirota strain belonging to L. casei as a common addition to dairy and yoghurt products. It's a well-studied species due to its wide potential in food, biopharmaceutical, and medical applications.

L. casei is the namesake for the Lactobacillus casei group (LCG), composed of the closely related L. casei, L. paracasei, and L. rhamnosus species. It is known for effective management of diarrhoea in children through its ability to influence gut microbiota and calm inflammatory markers.

Other benefits of L. casei include:

Positive effect on biomarkers associated with obesity and improved weight management

Potential tumour reduction in colorectal cancer in combination with fibre

Maintaining gut diversity and preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

4. Lactobacillus paracasei

L. paracasei is commonly found in the human gut and in naturally fermented raw dairy and vegetables. It has a wide range of probiotic applications and has been widely studied as part of the LCG.

Applications relating to L. paracasei include:

Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection by reducing its ability to bind to the stomach lining and reducing inflammation

Reducing bloating and abdominal pain associated with diverticular disease in combination with high-fibre diet

Antimicrobial activity against some gut pathogens including Yersinia, Shigella, and Listeria

5. Lactobacillus rhamnosus

L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) was the first Lactobacillus strain to be patented—in 1989. Over the past 30+ years, it has emerged as probiotic royalty. It readily survives stomach acid and bile, easily adheres to gut cells, and produces a gut-protective biofilm.

LGG promotes the survival of intestinal crypts (folds) and intestinal epithelial cells, inhibits pathogens like Salmonella, and promotes immune responses.

Additional benefits include:

Positive effect on brain function—affecting GABA receptors, decreasing anxiety and depressive behaviours

Reducing severity of gastro virus Rotavirus

Decreasing pain associated with IBS in children and improving glucose tolerance in pregnancy

6. Lactobacillus reuteri

L. reuteri is a powerful antimicrobial-producing probiotic that has undergone several name changes—from being wrongly labelled as L. fermentum in 1919, to L. fermentum biotype II in the 1960s, to L. reuteri in 1980, and now reclassified as Limosilactobacillus.

L. reuteri gets its species name from its potent antimicrobial by-product reuterin.

Key facts about L. reuteri:

Naturally found in breastmilk and passes to the child

Produces B12 (cobalamin) and B9 (folate)—B12 is actually vital to its own B12 production

Increases bile production and modulates gut microbes

7. Lactobacillus fermentum

Given its close relation to L. reuteri, L. fermentum also produces many antimicrobials and shares a similar renaming history—now reclassified as Limosilactobacillus, with some strains moved to the L. reuteri category.

L. fermentum strains can decrease blood cholesterol levels and help prevent alcoholic fatty liver disease, among other benefits:

Inhibits the attachment of pathogens in the gut

Reduces the incidence of gastrointestinal and upper respiratory infection in infants

8. Lactobacillus gasseri

L. gasseri is a normal inhabitant of the vagina. It produces the antibiotic lactocillin and gassericin A, making it an important player in vaginal and reproductive health.

L. gasseri has been found to help with weight loss. Daily consumption of L. gasseri BNR17, isolated from breast milk, may reduce body fat in those with obesity.

Other benefits include:

L. gasseri is an important lactobacilli found in vaginas of healthy women along with L. crispatus, L. jensenii, and L. iners

Inhibits the STD Trichomonas vaginalis

Reduces yeast infection Candida albicans biofilm production

9. Lactobacillus johnsonii

Another lactobacilli that contributes to a healthy vaginal microbiome, L. johnsonii can help maintain healthy gut lining function.

It has been shown to reduce the risk of developing diabetes and offer protection against obesity.

L. johnsonii also:

Reduces incidence of Staphylococcus aureus skin infection

Positively affects the immune system via tryptophan metabolism—an important neurotransmitter precursor for serotonin and melatonin

10. Lactobacillus salivarius

A native gut microbe, L. salivarius has a substantial body of research behind it. It has been shown to suppress pathogenic bacteria, alleviate inflammation, and reduce Group B Strep (Streptococcus agalactiae) risk in pregnant women.

Additional benefits:

Producing antibacterial compounds against the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes

Protecting the kidneys from toxic accumulation by alleviating gut dysbiosis

Inhibiting growth of the cavity-forming oral bacteria Streptococcus mutans

11. Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

Another renamed lactobacilli, L. d. bulgaricus was known simply as L. bulgaricus until 2014. It was discovered in 1905 in Bulgaria from a yoghurt sample and named accordingly.

It remains the main bacterium used in yoghurt fermentation (along with Streptococcus thermophilus) and is also used to ripen some cheeses and other fermented products. L. d. bulgaricus produces lactic acid and the aromatic compound acetaldehyde during yoghurt fermentation, giving yoghurt its typical aroma. Some strains also produce antibiotic compounds.

Research shows it can:

Enhance immunity in elderly individuals

Inhibit growth of increasingly drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

Have potential cholesterol-lowering effects in high-cholesterol diets

12. Lactobacillus brevis

The last lactobacilli on our list has also been renamed Levilactobacillus brevis. L. brevis is found naturally in the gut and many fermented foods like sauerkraut and pickles. It's also a common beer spoilage organism.

Kefir grains would not be possible without Levilactobacillus species. L. brevis and other levilactobacilli produce the polysaccharide compounds that form the structural network of kefir grains.

L. brevis also:

Protects against bacterial vaginosis and E. coli urinary tract infections

Has inflammation-reducing properties

Bifidobacterium

Bifidobacteria make up a dominant fraction of the gut microbiome (between 1–10%) and more so in infants (around 90%). They are a large family of probiotic bacteria most numerous in the bowel, lower intestines, and vaginal/genital area.

The majority of Bifidobacterium species have been found exclusively in the human and animal gut. It wasn't until 1974 that Bifidobacterium became a group on their own.

Bifidobacterium species degrade various sugars for energy including monosaccharides, galacto-, manno-, and fructo-oligosaccharides, and some species can ferment complex carbohydrates like arabinogalactan and arabic gum. Read more about prebiotics for Bifidobacterium here.

Bifidobacterium are seen in lower than optimal numbers in the following conditions:

Interestingly, research on the Hadza tribe in Tanzania showed that Hadza adults don't carry Bifidobacterium—similar reduced numbers are seen in populations with reduced dairy intake (e.g., vegans and Koreans).

13. Bifidobacterium animalis

B. animalis previously had two subspecies—Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. animalis—which have been contracted under the single B. animalis banner.

The strain B. animalis subsp. lactis CECT 8145 has been shown to decrease blood pressure and waist circumference significantly in women, with the added benefit of increasing Akkermansia levels.

General benefits of B. animalis include:

Effectively treating diarrhoea in infants and children from Rotavirus

Improving constipation outcomes in adults

Reducing IBS symptoms in constipation-dominant sufferers

14. Bifidobacterium longum

B. longum is commonly seen on gut microbiome test reports. Even when other Bifidobacterium species are absent, B. longum often remains—sometimes in high numbers.

This may be partly due to the 2002 name change which unified three previously distinct species: B. infantis, B. longum, and B. suis. These have now become subspecies of B. longum, though B. infantis deserves special mention and is discussed below.

Notable benefits of B. longum include:

Supporting the growth of the butyrate (SCFA) producer Eubacterium rectale

Effectiveness in treatments of ulcerative colitis

Immune system regulation and decreasing severity of mild colds and flu

15. Bifidobacterium infantis

As its name suggests, B. infantis (now B. longum subsp. infantis) is an important species during infancy. Together with B. bifidum, these species are crucial in establishing infant microbiome foundations because they are genetically programmed to digest human milk.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) in breast milk are babies' first prebiotics, designed to supply these remarkable and adaptable species and begin the groundwork for a healthy gut start to life.

B. infantis has been shown to:

Accelerate infant immune system response to illness

Improve early gut lining barrier function and produce the SCFA acetate

16. Bifidobacterium bifidum

B. bifidum was first isolated in 1900 and named in 1924. This adaptable infant gut forager can switch its metabolism from digesting HMOs to mucin (mucus) degradation—meaning that after a child is weaned, it persists with a different food source.

It is so far the only Bifidobacterium species capable of degrading both, making B. bifidum a key player in healthy gut development.

Key functions include:

Maintaining the integrity of the gut lining and consequently reducing inflammation

Reducing inflammation associated with psoriasis and chronic fatigue syndrome

17. Bifidobacterium breve

Another beneficial Bifidobacterium in infants (and adults), B. breve is a dominant species in the gut of breast-fed infants. It has been isolated from breast milk itself and has been shown to promote development of a healthy microbiome.

It is often used together with other species for treatment of ulcerative colitis, Helicobacter pylori, and IBS, as well as for treatment and prevention of many paediatric conditions including diarrhoea, colic, celiac disease, obesity, allergies, and neurological disorders.

B. breve has also been linked to better adult weight-loss outcomes in obesity management and even Alzheimer's disease.

Other benefits include:

Reduced risk of asthma and atopic dermatitis

Potential to outcompete coliforms or other non-beneficial gut microbes

Other Probiotic Species

These organisms are common additions to probiotic supplements and foods that don't fall into the lactobacilli or bifidobacteria categories.

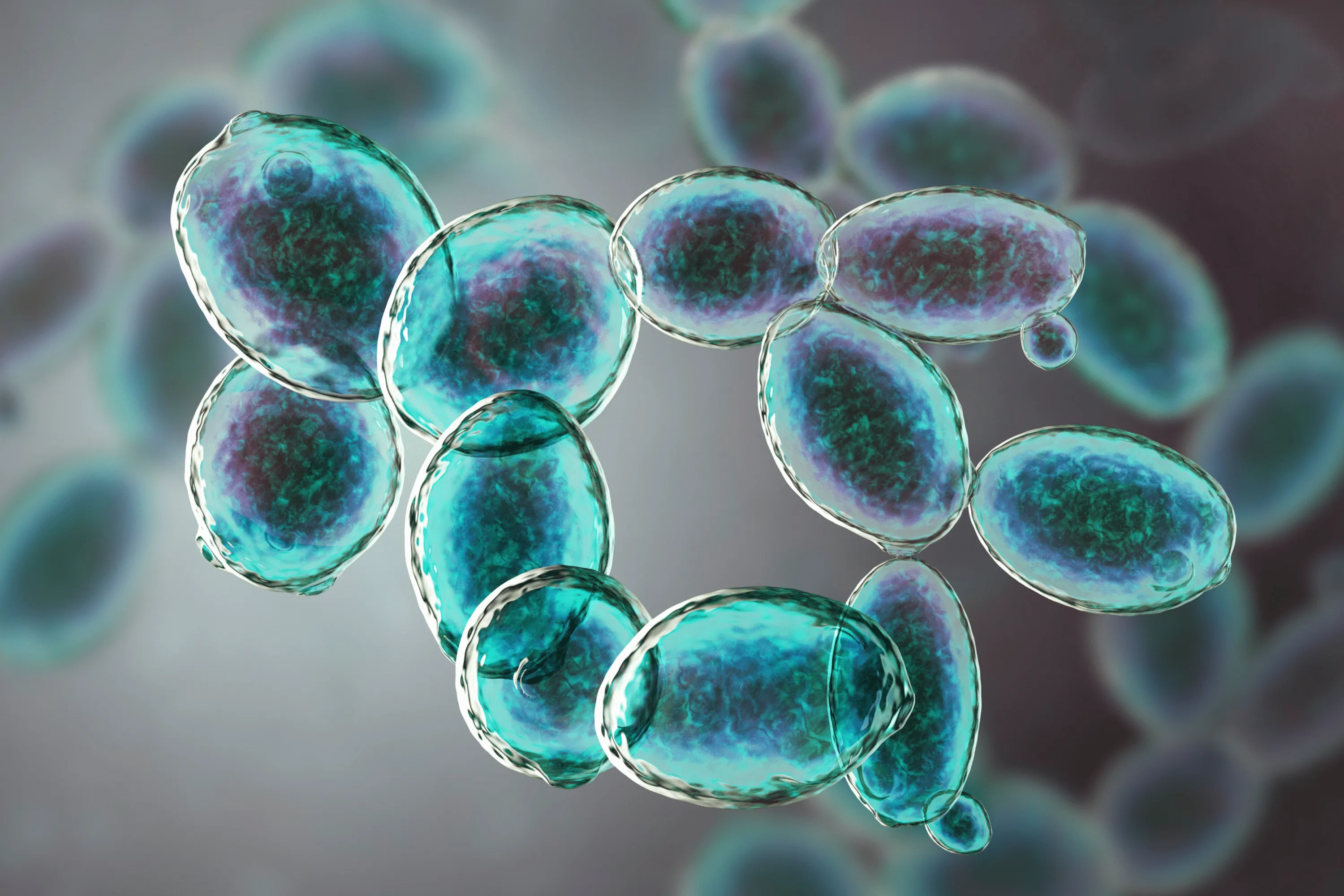

18. Saccharomyces boulardii

S. boulardii is the only non-bacterial probiotic on this list—it's a yeast. Saccharomyces is the genus responsible for much of the world's fermentation (think bread and beer) thanks to S. cerevisiae.

S. boulardii is in fact a strain of S. cerevisiae—its proper name is S. cerevisiae var boulardii, and it's genetically closest to the yeast used in wine making.

S. boulardii was first discovered in 1923 by French scientist Henri Boulard from lychees. He noted that in China, cholera diarrhoea was treated with lychee extract—from this, he isolated the yeast.

S. boulardii is used to treat a number of diarrhoeal illnesses in both adults and children. There is also evidence that S. boulardii inhibits pathogenic properties of Candida albicans, including biofilm formation, adhesion to the gut lining, and filamentation.

19. Streptococcus thermophilus

Also known as Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus, this lactic-acid bacteria (LAB) is widely used in milk fermentation products, most commonly with L. d. bulgaricus.

This Streptococcus is generally believed to be safe (compared with other Streptococcus species) due to its lack of a gene for attaching to the gut surface. However, individual assessment of your personal gut microbiome is always recommended.

S. thermophilus is mostly studied in combination with other species of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and may provide improved symptoms for gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS and diarrhoea.

20. Enterococcus faecium

Another LAB, E. faecium is a known gut coloniser but can also act as a pathogen. They break down proteins and ferment carbohydrates and are a common addition to probiotic formulations.

E. faecium should not be confused with E. faecalis (formerly known as Streptococcus faecalis). E. faecium is most commonly pathogenic in hospital patients and is thought to carry low risk to the wider community.

Probiotic studies have found E. faecium to assist in diarrhoeal treatment and prevent the growth of several virulent bacteria including Staphylococcus and Listeria.

21. Bacillus coagulans and Bacillus subtilis

Bacillus are often referred to as soil bacteria because they do not naturally colonise the human gut—they are most at home in soil. These bacteria produce small spores that ensure they are not affected by stomach acid on the journey to the gut, and have been found to offer probiotic benefits.

Although not all members of the Bacillus family are beneficial, some Bacillus species are thought to be effective with allergies and autoimmune conditions. They can also produce antibacterial agents and other helpful active compounds.

Studies have shown B. coagulans to alleviate IBS symptoms in elderly patients, and B. subtilis to inhibit cancer cells.

22. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor)

Not all E. coli strains are pathogenic. E. coli Nissle 1917 is actually a potent probiotic, covered extensively in our article The E. coli Strain "Nissle 1917" (Mutaflor): A Powerful Probiotic.

Mutaflor is the trade name for an E. coli strain isolated in World War I in 1917 by Alfred Nissle. He found that dysentery didn't occur in a particular soldier carrying this strain and used it to treat those with symptoms.

It has been extensively researched and found effective for IBD (including Crohn's and ulcerative colitis), leaky gut, IBS, constipation, diarrhoea, and increasing serotonin.

Using Mutaflor can be a powerful approach to gut healing but needs to be used with a targeted plan for best results.

Conditions and Probiotic Reference Chart

This table lists common conditions and some of the Lactobacillus probiotics (and combinations) that have been found to support them. Note that many studies examine species in combination rather than singly—a plus sign (+) indicates combination formulations.

Condition | Beneficial Probiotic Species |

Gastrointestinal Conditions | |

H. pylori infection | L. johnsonii, L. gasseri, L. reuteri, L. brevis, S. thermophilus + L. reuteri, L. acidophilus + L. casei + B. longum + S. thermophilus |

Diarrhoea | |

Constipation | |

Ulcerative colitis | |

Diverticulitis | |

Irritable Bowel Syndrome | |

Traveller's Diarrhoea | |

Infant Conditions | |

NEC | |

Dental Conditions | |

Gum Disease (Periodontal) | |

Allergy Conditions | |

Hay Fever | |

Dermatitis | |

Allergy Prevention | |

Other Conditions | |

Mastitis | |

UTIs (Urinary Tract Infections) | |

High Cholesterol | |

Vaginal yeast/bacterial infection | L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus + L. fermentum, L. acidophilus, L. casei |

Diabetes (Type 2) |

What About Fermented Foods?

Fermented foods do provide a range of beneficial microorganisms. They are the traditional and original preservation solution—fermenting presumably originated as a method to store food over long periods after harvest.

Typical fermentation works on the principle that native (or introduced) microorganisms produce acids that prevent the growth of spoilage organisms—generally lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus.

There is variation in species present across different fermented foods. Sauerkraut, for instance, has a different microbe profile batch to batch when made at home, and even more variation occurs across different climates.

Fermented foods are a good natural complement to probiotic supplementation, though we caution against excessive consumption of fermented beverages due to:

Frequently high sugar content

Often high yeast levels (kombucha SCOBYs, for example, are yeast-dominant)

Both of these factors can be problematic for those with leaky gut symptoms.

The best approach is to introduce fermented foods slowly and watch for negative symptoms. These foods are medicinal in nature and should be respected as such.

If buying fermented foods, always check that they haven't been pasteurised or heat-treated—this processing intentionally kills all the live beneficial microbes.

Recipes to try:

Using Probiotics as a Healing Tool

Probiotics can be a powerful supporting tool for your gut and healing journey. There has been significant research into the strains mentioned here, and studies continue to emerge.

However, in excess, some probiotics may not be beneficial for your unique microbiome (or at this particular time), and the only way to know this is by testing your gut bacteria.

The importance of working with an experienced professional who tests cannot be overstated. Trial and error is not a long-term solution to any health problem—but identifying and resolving the root cause is.

Ready for a Testing-Guided Approach?

If you're considering probiotics as part of your gut health strategy, comprehensive testing provides the foundation for effective, targeted supplementation.

At Prana Thrive, we use metagenomic sequencing—the most comprehensive gut testing available—to identify exactly what's happening in your microbiome. This includes bacteria, fungi, parasites, and functional markers that reveal not just what's present, but what those organisms are doing.

Every test is reviewed by Amanda (who has personally analysed over 2,000 individual microbiome tests) with scientific oversight from Victoria, our in-house microbiologist. This combination of clinical pattern recognition and microbiological expertise means your probiotic recommendations are based on your unique microbial fingerprint—not generic protocols.

Our AIM Method™ (Analyse → Integrate → Monitor) ensures:

Analyse: Comprehensive testing reveals your starting point, including which probiotics you may need, which you may already have in excess, and what order interventions should occur

Integrate: A personalised protocol incorporating the right probiotics at the right time, alongside dietary and lifestyle modifications

Monitor: Follow-up testing and consultations to track progress and adjust your protocol as your microbiome evolves

Book a free 15-minute evaluation call to discuss your symptoms and find out if our approach is right for you.

We work with a limited number of clients each month to ensure everyone receives the attention they deserve. If you're ready for a testing-guided approach to probiotics—not just more guesswork—book your call now.

Book Your Free Evaluation Call

Related Articles:

Service Pages: