The Ultimate Prebiotic A-Z Guide

Plus 31 of the Most Common Prebiotics

Author:

Amanda Ledwith, BHSc Naturopathy

Last Updated:

23 Jan 2026

Reading Time:

20 mins

Categories:

Gut Health

prebiotics

What You'll Learn

Prebiotics are nutrients that feed beneficial gut bacteria, which in turn produce health-promoting compounds like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Unlike probiotics (the bacteria themselves), prebiotics are the food source that allows beneficial bacteria to thrive and multiply.

The most common prebiotics include fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) found in chicory root and Jerusalem artichoke, galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) in legumes, and beta-glucans in oats and barley. While increasing prebiotic intake benefits most people, those with IBS or FODMAP sensitivities may need a more targeted approach—testing your gut microbiome provides the data needed to determine which prebiotics will support your specific bacterial populations without triggering symptoms.

What Are Prebiotics?

Prebiotics have been part of the human diet since the beginning of time—you've likely consumed some today. It's only since discovering that our gut bacteria utilise them that we've begun to understand their true health-promoting potential.

The concept was first proposed in 1995 by Glenn Gibson and Marcel Roberfroid, who described prebiotics as:

"A non-digestible food ingredient that beneficially affects the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacteria in the colon, and this improves host health."

This definition remained unchanged until 2008, when The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) recognised that the historic definition excluded many potential prebiotic substances. The updated "dietary prebiotic" definition now reads:

"A selectively fermented ingredient that results in specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota, thus conferring benefit(s) upon host health."

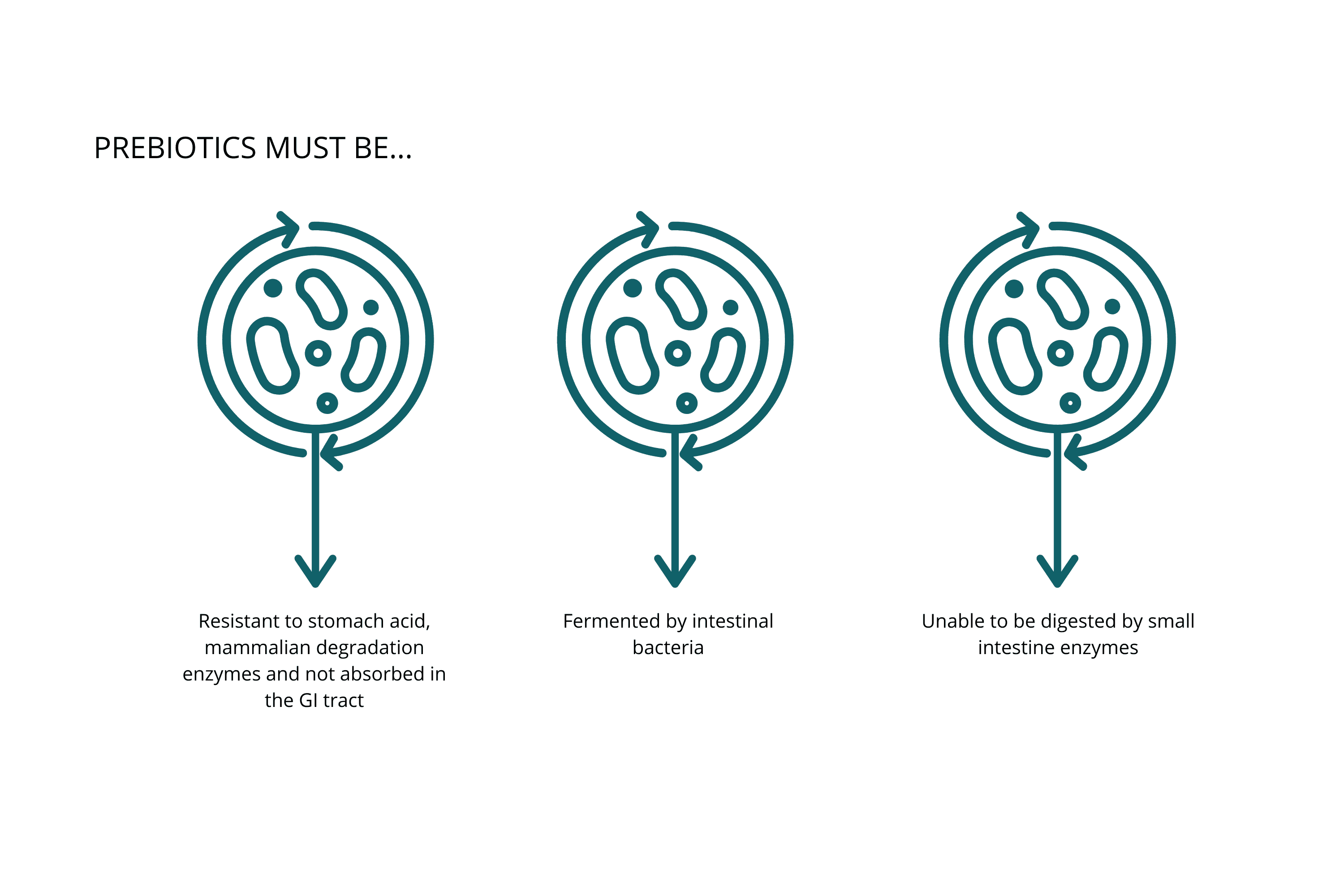

The ISAPP also stipulated a range of criteria that prebiotics must meet:

Resistant to stomach acid, mammalian degradation enzymes, and not absorbed in the GI tract

Fermented by intestinal bacteria

Unable to be digested by small intestine enzymes

Prebiotics are further defined as different from fibre—not all prebiotics are carbohydrates, and not all fibres are prebiotic. However, many fibre types ultimately have a similar prebiotic effect.

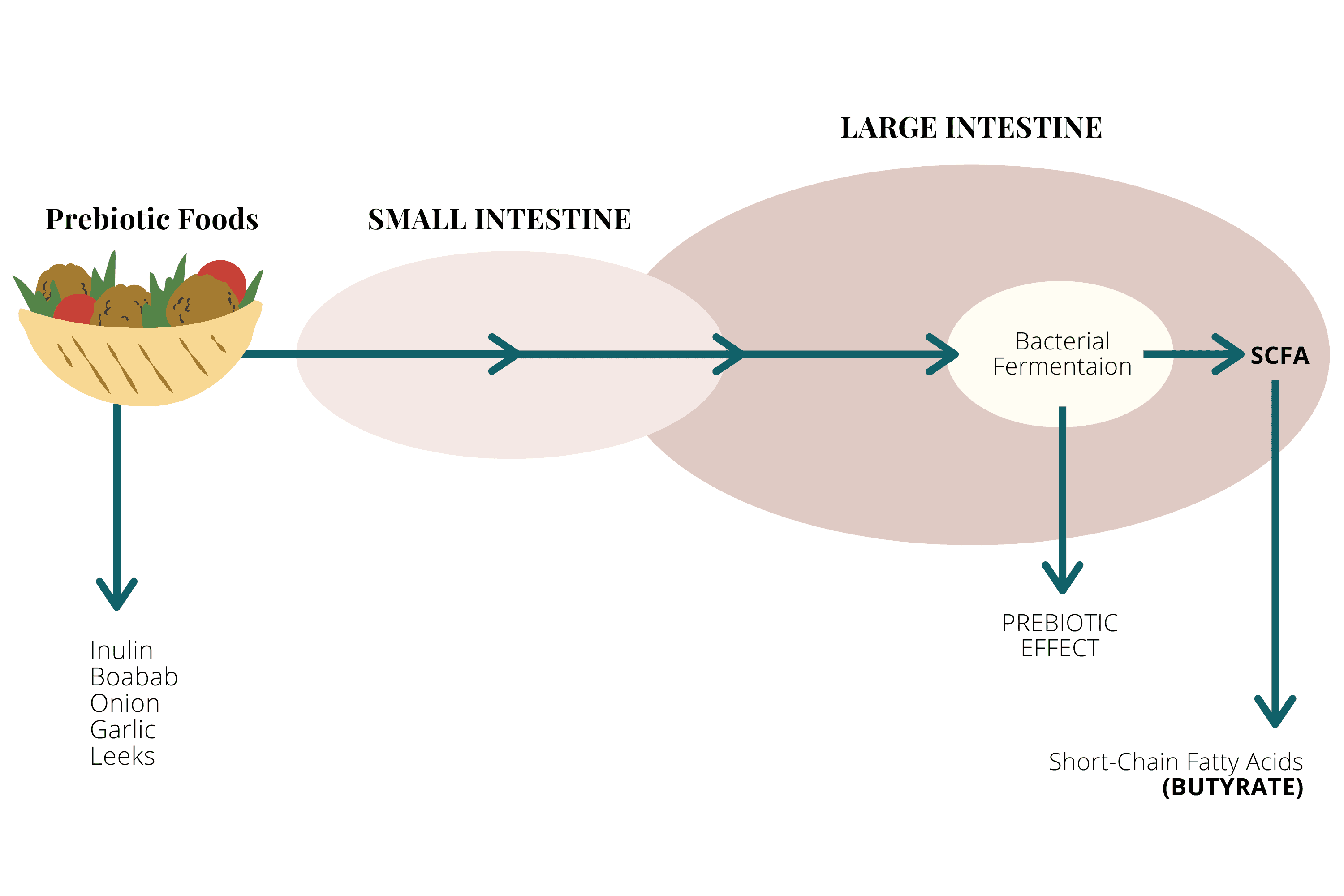

In essence: prebiotics are substances that feed beneficial bacteria. Those bacteria then produce health-promoting compounds such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), often referred to as postbiotics.

Whether we classify something as a prebiotic, fibre, or resistant starch matters less than whether it benefits your microbiome and health.

How Prebiotics Provide Health Benefits

Prebiotics, simply by their intestinal presence, influence the composition and function of gut bacteria. They serve as an energy source for many beneficial bacteria—essentially, their food.

When prebiotics are present, the fermenting bacteria that encounter them in the gut can increase replication, changing the composition of your microbiome. It's a matter of supply and demand: the more food (energy) available, the more bacteria can multiply.

The beneficial aspect is that most prebiotic-degrading bacteria produce our gut health champion fermentation by-product—SCFAs.

SCFAs offer significant benefits including:

Enhanced immune function

Improved cardiovascular, metabolic, and general health

Higher lean body mass

Enhanced cognitive function

Elevated mood

Prebiotics may also provide favourable metabolites for other beneficial bacteria through a process called cross-feeding.

However, there is no one-size-fits-all prebiotic.

Which Prebiotic Is Best?

Different bacteria can only ferment certain prebiotic substances, based primarily on the genes they possess (their enzymes do the work breaking them down) and the length of the prebiotic molecule.

For example, the prebiotic inulin (a type of FOS) can only be fermented by a limited number of bacterial species because it's a long molecule with a DP <60 and more complex structure.

Note: DP indicates the degree of polymerisation—how many repeating units make up the molecule.

In contrast, other FOS (fructo-oligosaccharides) are smaller at DP <10, so a larger number of bacterial species can ferment this prebiotic type.

This is important when choosing prebiotics, especially in supplement form: there is no single best prebiotic for all bacteria.

🔬 VICTORIA'S EXPERT INSIGHT

"When I review microbiome test results, I pay close attention to which bacterial populations are low before recommending specific prebiotics. For example, if someone is low in Bifidobacterium but has adequate Bacteroides, recommending FOS or inulin makes sense because these selectively feed bifidobacteria. But if someone has SIBO or significant dysbiosis, adding prebiotics without addressing the underlying imbalance can actually feed problematic bacteria and worsen symptoms. This is why we test first—the data tells us exactly which prebiotics will help and which might cause problems for your specific microbial ecosystem."

— Victoria, Microbiologist

Book Your Free Evaluation Call

Classification of Prebiotics

Prebiotics are grouped based on their chemical or molecular structure. The majority are a subset of carbohydrates called oligosaccharide carbohydrates—"saccharide" meaning sugar and "oligo" meaning a few. So: a few sugar molecules joined together, typically 3 to 10.

Carbohydrate classification:

Monosaccharides – single sugar units (e.g., fructose, glucose)

Disaccharides – 2 monosaccharide units joined (e.g., sucrose, lactose)

Oligosaccharides – 3 to 10 monosaccharides

Polysaccharides – more than 10 (often hundreds) monosaccharides (e.g., starch, fibre)

Prebiotic Groups Overview

Prebiotic Group | Common Types | Food Sources |

Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) | Fructans, Inulin, Oligofructose, Oligofructans | Chicory, Onions, Asparagus, Leeks, Jicama, Jerusalem artichoke, Yacon, Agave |

Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) | Lactose, Raffinose, Stachyose, Arabinogalactan, Gum arabic (Acacia), Guar gum, Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMO) | Legumes, Beans, Jerusalem artichoke, Chickpeas, Breast milk |

Mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) | Konjac plant, Saccharomyces boulardii, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | |

Xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS) | Xylose, Xylan | Plant fibre, Seaweeds, Microalgae |

Pectic oligosaccharides (POS) | Pectin, Citrus pectin | Apples, Oranges, Lemons, Limes, Grapefruit |

Plant Polyphenols | Phenolic acids, Stilbenes, Resveratrol, Flavonoids, Tannins | Vegetables, Fruits, Cereals, Tea, Coffee, Dark chocolate, Cocoa powder, Wine, Herbs and spices |

Fermentable Fibres | Resistant starch, Fibre, Cellulose, Lignin, Beta-glucans | Green bananas, Sweet potato, Cassava (tapioca), Cooked and cooled rice, Leafy greens, Nuts, Berries, Seeds, Pears/Apples, Coconut, Broccoli, Cabbage, Brussels sprouts, Beetroot |

While fibre and resistant starch aren't strictly "prebiotics" by definition, they offer comparable benefits for gut health.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMO) deserve mention as a seemingly miraculous prebiotic specifically designed to seed gut-supportive Bifidobacterium in infants.

The 31 Top Prebiotics You Should Know About

1. Chicory Root

Chicory is a leafy green herb—its leaves are edible and used in salads, while its roots have been valued for decades as a coffee substitute. More recently, chicory root has become popular as an excellent source of prebiotics.

Roughly 50% of the fibre in chicory root is the prebiotic fibre inulin—a type of FOS (fructose polymer) found widely in nature as a plant carbohydrate storage molecule.

This well-studied prebiotic has been found to nourish gut bacteria, improve digestion, relieve constipation, and increase bile production. In the microbiome, inulin consumption has been associated with encouraging beneficial Bifidobacterium while reducing the abundance of Bilophila—a group containing known non-beneficial bacteria.

Chicory is also recognised as a powerful antioxidant and liver support.

2. Jerusalem Artichoke

Also known as "sunroot," "sunchoke," or "earth apple," these tubers are the root system of a beautiful yellow mini sunflower.

With 2 grams of fibre per 100 grams, and approximately 80% of that being inulin, Jerusalem artichokes are an excellent wholefood prebiotic source. They have been shown to increase beneficial bacteria, strengthen the immune system, and prevent metabolic conditions like type-2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in animal models.

3. Leeks

Leeks belong to the Allium group of plants, which includes onion, garlic, shallots, spring onions, and chives. They are thought to be high in inulin and contain many of the same beneficial nutrients found in onions and garlic.

Additionally, leeks are an excellent source of vitamin K—important for blood clotting and bone health.

4. Asparagus

Asparagus is another natural source of the prebiotic inulin. Although lower in inulin than chicory root and Jerusalem artichoke, it's also a nutrient powerhouse—high in fibre, protein, and notable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds including saponins, flavonoids, quercetin, vitamin C, and zinc.

Asparagus is also high in folate (vitamin B9), essential for blood cell formation, liver health, and prevention of neural tube defects during pregnancy. One cup of asparagus provides 67% of the recommended daily intake of folate.

5. Bananas

Green bananas (or plantains) are an excellent resistant starch source. Our green banana and cassava pancakes offer a fibre-packed alternative to wheat-based options.

Bananas also contain small amounts of inulin and have been shown to reduce bloating in those with gastrointestinal problems. Green banana flour is available in most supermarkets and health food stores—it makes an easy substitute in baking for a prebiotic and resistant starch boost.

6. Soybeans

Soybeans (edamame) are a long-held staple in Asian diets with well-studied health benefits. They are also a source of prebiotic oligosaccharides.

Research suggests that soybeans increase the abundance of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli while decreasing the proliferation of the pathogenic Clostridium perfringens. Soybeans have also been shown to improve immune function by enhancing critical immune cell activity.

7. Jicama Root

Pronounced HEE-kah-ma, jicama is an edible root vegetable originating from Mexico. This high-fibre yam-like tuber is a good source of inulin and high in vitamin C—one cup provides 44% of the RDI.

Studies have shown jicama fibre helps prevent excessive blood glucose levels and assists in weight maintenance.

8. Dandelion Greens

The leaves of dandelion contain 4 grams of fibre per 100 grams and are a potent source of inulin.

Dandelion greens are also known for other health-giving qualities—anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and general health tonic properties.

9. Sweet Potato, Yams, and Maca

Sweet potatoes are both resistant starch and prebiotic powerhouses. Whether purple, orange, or yellow, studies have shown that sweet potato is a great source of inulin. They are also excellent sources of vitamin C, potassium, and manganese—and one cup provides 769% of the daily vitamin A intake.

Yams (lumpy brown tubers) also offer an inulin bonus. Research has shown the prebiotic potential of yam with SCFA-boosting powers potentially better than commercial inulin alone—another reason wholefood sources are preferable.

Maca, another inulin-rich tuber, has been shown to increase growth of B. longum and L. rhamnosus more than inulin alone, with additional anti-inflammatory benefits.

Try our sweet potato rosti recipe for inspiration.

10. Burdock Root

Burdock is the root harvested from the Arcticum plant family and a common addition in Japanese cuisine and traditional Chinese medicine.

Burdock inulin is a well-studied prebiotic shown to stimulate the growth of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. Burdock root contains some FOS and approximately 4 grams of fibre per 100 grams.

It also contains antioxidant compounds including quercetin, phenolic acids, and luteolin. Burdock root can be consumed as tea, taken as a supplement, or eaten as a vegetable.

11. Yacon Root

Similar to sweet potato, yacon root is rich in fibre, particularly inulin and FOS. Yacon is the root of a daisy traditional in South America—also known as the Peruvian ground apple for its sweet flavour.

Yacon promotes SCFA levels by encouraging growth of microbes that utilise its FOS as energy. Consumption has been shown to have positive effects on colorectal cancer, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

12. Garlic

A well-known health elixir, garlic contains both inulin and FOS prebiotics. Garlic has been found to stimulate the growth of gut-protective Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides in culture studies.

Extracted garlic has been widely studied for potential benefits in heart disease and asthma, in addition to its known antioxidant and antimicrobial effects.

13. Onions

Like garlic, onions contain both inulin and FOS. The FOS present in onions has been found to stimulate immune cells. Onions are also rich in the prebiotic-mimicking flavonoid quercetin.

It is recommended that 4 grams of FOS per day offers sufficient prebiotic benefits—primarily from Bifidobacterium selectively fermenting FOS.

Raw consumption maximises benefits—try our Peruvian Snapper Ceviche With Fresh Lime and Chilli featuring raw red onion.

14. Larch (Arabinogalactan)

Larch, also called arabinogalactan after the prebiotic type it contains, is a starch-like chemical found in many plants but highest in larch trees.

Arabinogalactan has documented health benefits including regulation of natural killer T cells in the immune system. Many chronic diseases such as chronic fatigue, viral hepatitis, and autoimmune diseases are associated with decreased natural killer T cells—arabinogalactan acts to improve these levels.

In addition to being a potent prebiotic, larch is used as a food additive for its binding, stabilising, and sweetening properties.

15. Radishes

Another arabinogalactan source, radishes come in many varieties—from traditional pink bulbs to the massive white daikon prized in Asian cooking. All are excellent sources of minerals, nutrients, and prebiotics.

Of particular scientific interest is the anti-cancer potential of radish and associated arabinogalactans.

An easy way to increase radish arabinogalactan is through kimchi—try our delicious kimchi recipe.

16. Guar Gum

Guar gum is the high-fibre, GOS (galactomannan) prebiotic-rich extract of the guar bean. It has long been used as a stabiliser and thickener in food and industrial applications (E412).

While extracted from a natural source, highly processed guar gum is far removed from its natural state. It is undeniably a prebiotic substance, but wholefood sources are generally preferable.

17. Acacia (Gum Arabic)

Acacia gum is the resin or sap of two species of acacia tree. The gum is primarily harvested from Sudan and is a complex mixture of sugars and proteins (E414).

It's commonly used in confectionery, soft drink syrup, as a binder in various industrial applications, and is one of the best-studied prebiotics known to increase Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli concentrations—with effects higher than inulin alone.

18. Apples

The prebiotic found in apples is pectin (POS), known for its gelling qualities in jam-making. Pectin makes up approximately 50% of an apple's total fibre content and is commercially produced from citrus fruits.

Microbiome studies on pectin indicate that Bacteroidetes thrive on pectin whereas Firmicutes generally don't. The exception is Eubacterium eligens, which can degrade apple pectin and promotes anti-inflammatory effects. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, an anti-inflammatory bacterium and healthy gut indicator, can also degrade pectin.

There really is truth to "an apple a day."

19. Barley

Barley contains between 3 and 8 grams of the prebiotic beta-glucan per 100 grams. Beta-glucans are polysaccharides made up of repeating glucose units, occurring naturally in the cell walls of cereal grains, bacteria, and fungi (including edible mushrooms and yeasts). They were first discovered in fungi and then in barley.

As with all prebiotic fibre, beta-glucans resist digestion until reaching the lower digestive tract where the microbiome ferments them. Beta-glucans have been shown to increase Bacteroides and Prevotella in the gut.

20. Oats

Following beta-glucan-rich barley, oats are equally well-known for their beta-glucan content.

Particular interest arose after a 1981 study demonstrated LDL cholesterol reduction in those consuming oat bran. The beta-glucan in oats comes from the endosperm (innermost portion) of the oat kernel, which also contains some resistant starch.

Oats have been shown to help control blood sugar, increase SCFA concentrations, and encourage the growth of bifidobacteria.

21. Mushrooms

Mushrooms have been long recognised as a superfood—many ancient cultures revered edible fungi for their medicinal and nutritive properties. In addition to proven anti-allergic, anti-cholesterol, and anti-cancer properties, mushrooms are rich in many prebiotic carbohydrates:

Chitin

Hemicellulose

Beta and alpha-glucans

Mannans

Xylans

Galactans

Mushrooms have been found to positively affect many beneficial gut bacteria while decreasing non-beneficial bacteria like Citrobacter and reversing dysbiosis.

Try our dairy-free mushroom soup for inspiration.

22. Konjac

Konjac, also known as elephant yam, is a tuber containing glucomannan—a MOS. It's a staple in Asian cuisine and now available as an alternative to traditional rice, noodles, and pasta.

Note: any prebiotic taken in excess can have significant effects on bowel function—introduce gradually.

23. Yeast

Similar to mushrooms, yeast cell wall structures are rich in prebiotic beta-glucan. The beta-glucans found in grains like barley and oats are also found in fungi—Aspergillus and Saccharomyces.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the yeast used in modern breadmaking and brewing. Health effects of beta-glucans include immune system activation, anti-cancer applications, dental treatment of gum disease, and allergic disease management.

Note: some individuals are sensitive to yeast, especially those with leaky gut.

24. Chia Seeds

Chia seeds are a true superfood and excellent prebiotic. This ancient staple is high in protein, full of fibre (including mucilage prebiotics), and a great source of omega-3 and omega-6.

Recent studies have shown that the mucilage gums in chia promote the growth of gut bacterial groups such as Enterococcus and Lactobacillus.

Chia seeds are an excellent grain-free alternative and reliable egg replacer in baking due to their binding mucilage properties. Try our Chia Berry Slice.

25. Flaxseeds

Flaxseeds are a mucilage gum prebiotic, similar to chia. Combined ground flax and chia make an excellent egg substitute with a fibre and prebiotic boost.

Studies have shown flaxseeds increase beneficial bifidobacteria and their SCFA metabolites, as well as the gut-lining champion Akkermansia.

Flaxseeds are also high in general fibre, omega-3s, and alpha-linolenic acid. Try our Cassava and Flaxseed Bread.

26. Wheat Bran

Wheat bran is the outermost husk of a wheat grain—the reason whole grain is preferable to white. It's an excellent source of fibre, including AXOS (arabinoxylan oligosaccharides), which comprises nearly 70% of its fibre content.

AXOS has been shown to boost Bifidobacteria levels and assist with digestive issues, and even demonstrate anti-cancer properties.

27. Seaweed

Seaweed contains 50–85% water-soluble fibre including the prebiotic XOS (xylan oligosaccharides).

The prebiotic effects of seaweed have been extensively researched and offer many gut health benefits including decreasing harmful gut colonisers like streptococci while increasing lactobacilli and the Bacteroides-Prevotella group.

28. Crickets

An option you may not have considered—crickets and other insects are now being farmed as a sustainable, livestock-free protein source. These common street foods in some Asian cultures are appearing in health stores worldwide as powdered forms.

Crickets contain prebiotic cell wall structures like chitin and have been shown to have significant effects on gut microbes. However, the results are mixed: cricket consumption has been found to decrease Lactobacillus (including L. reuteri) and Oxalobacter formigenes while increasing Streptococcaceae and Bifidobacterium animalis.

These findings highlight the importance of testing your gut bacteria before making significant dietary changes—what benefits one person may not suit another.

If you're interested in gut microbiome testing, we offer comprehensive programs to help you understand your unique microbial profile.

29. Baobab Fruit Pulp

The baobab tree—with its distinctive bulbous trunk and sparse branches—produces fruit composed of over 50% fibre. This completely natural wholefood has many proven benefits including adaptogenic properties, a low GI, and satiety induction.

It's rich in vitamin C, calcium, iron, magnesium, and polyphenols.

Baobab fruit is part of the ancient Hadza hunter-gatherer diet, which has received significant research attention for its extraordinary gut microbiome diversity.

30. Lucuma Powder

Lucuma (not to be confused with jicama) is a sweet fruit native to Peru, often described as tasting like sweet potato crossed with butterscotch—also known as 'Gold of the Incas.'

This ancient staple has prebiotic properties due to its high fibre content and associated gut microbe and SCFA benefits. Lucuma is rich in antioxidants and vitamin C, helps maintain blood sugar, and promotes heart health when substituted for sugar in baking.

31. Psyllium Husk

Originating centuries ago in traditional Indian Ayurvedic medicine, psyllium husks are the husks from around the seed of Plantago ovata, commercially produced specifically for its mucilage.

The resulting dietary fibre is commonly used to relieve symptoms of both constipation and mild diarrhoea, and is thought to lower cholesterol and blood sugar.

Psyllium has been shown to increase butyrate-producing bacteria including Lachnospira, Roseburia, and Faecalibacterium.

Prebiotic Wholefood Sources Summary

Vegetables | Fruits | Other Sources |

Artichoke Hearts, Asparagus, Beetroot, Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts, Burdock Root, Cabbage, Capsicum, Carrots, Cauliflower, Chicory Root, Cucumbers, Daikon Radishes, Dandelion Greens, Fennel Bulb, Garlic, Ginger Root, Hearts of Palm, Jicama, Konjac Root, Leeks, Mushrooms, Onions, Peas, Radishes, Sweet Potatoes, Yams | Apples, Avocado, Bananas, Berries, Cherries, Citrus, Coconut (meat & flour), Green Bananas, Kiwifruit, Mango, Olives, Pears, Tomatoes | Barley, Beans, Chia Seeds, Chickpeas, Dark Chocolate, Flax Seeds, Hemp Seeds, Honey, Legumes, Oats, Psyllium Husk, Pumpkin Seeds, Quinoa, Seaweed, Soybeans, Wild Rice, Wheat bran |

Common Prebiotic Supplements

For those interested in supplemental forms, common prebiotics found in capsules include:

Inulin-FOS

Inulin

Acacia fibre

Artichoke fibre

Green banana fibre

Chicory Root Powder

Citrus Pectin

XOS, GOS, MOS, TOS, FOS

Baobab powder

Lactulose

Pectin

Guar gum

Arabinogalactan

These may be listed as ingredients in supplements, often in combination.

FODMAPs and Prebiotic Intolerance

An important consideration: many prebiotic-rich foods can trigger symptoms in people with IBS or FODMAP sensitivity.

What Are FODMAPs?

FODMAP stands for:

F = Fermentable

O = Oligosaccharides

D = Disaccharides

M = Monosaccharides

A = And

P = Polyols

Many of these terms describe prebiotics and their oligosaccharide molecular structures. By nature, these structures are difficult to digest, absorb water, and can only be digested in the lower intestine by gut bacteria.

FODMAP is a relatively recent term coined by researchers at Monash University in 2006 as a dietary treatment specifically for those with IBS.

People with damage to their gut lining and dysbiosis, such as those with irritable bowel syndrome, suffer from maldigestion symptoms of gas, bloating, discomfort, and diarrhoea—and subsequently find it difficult to digest FODMAP-rich foods and prebiotics.

Which Prebiotics Are FODMAPs?

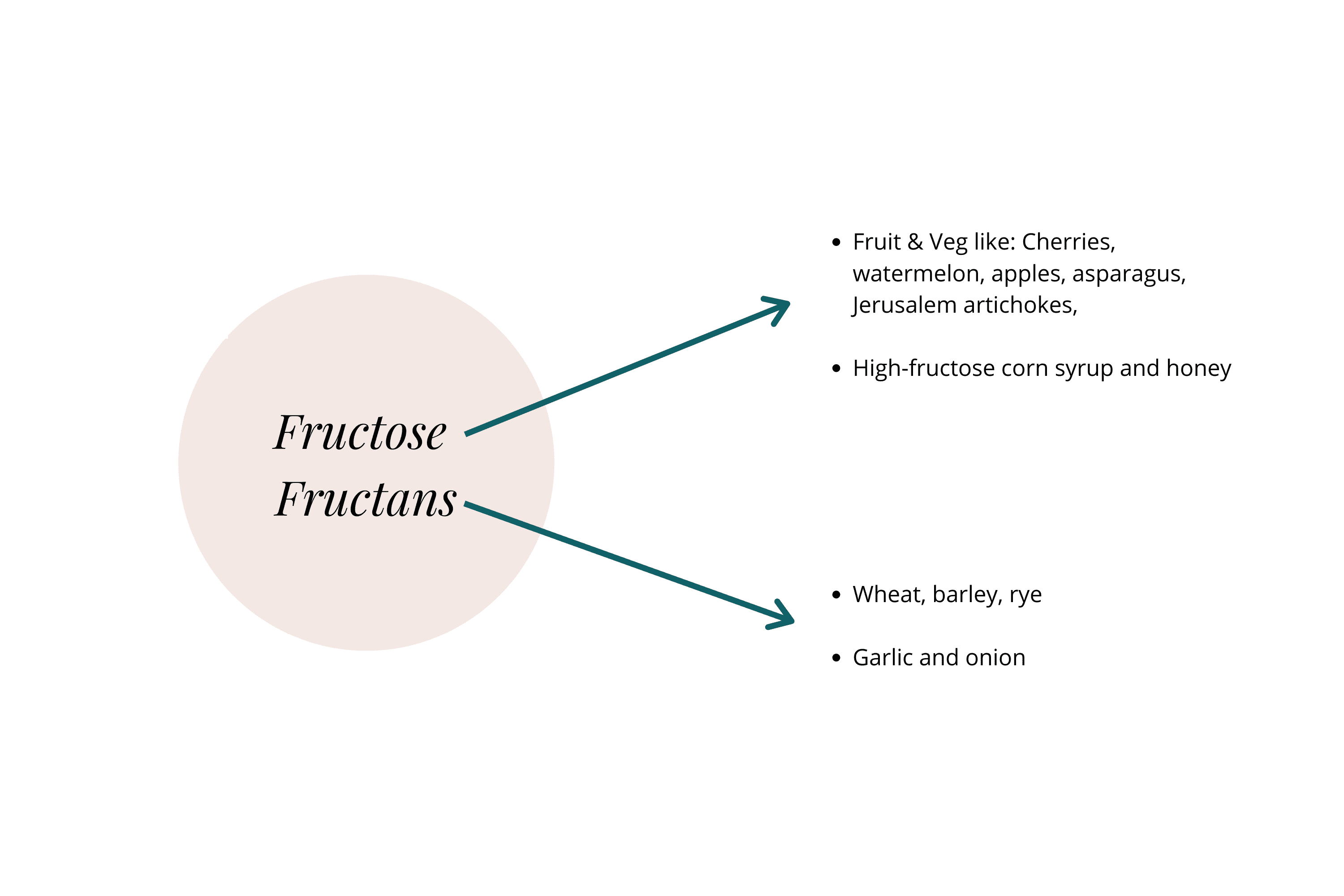

Fructose and fructans: Found in many fruits (cherries, watermelon, apples), some vegetables (asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes), high-fructose corn syrup, and honey. Fructans (FOS) are found in gluten-containing grains (wheat, barley, rye) and various fruits and vegetables (garlic, onion).

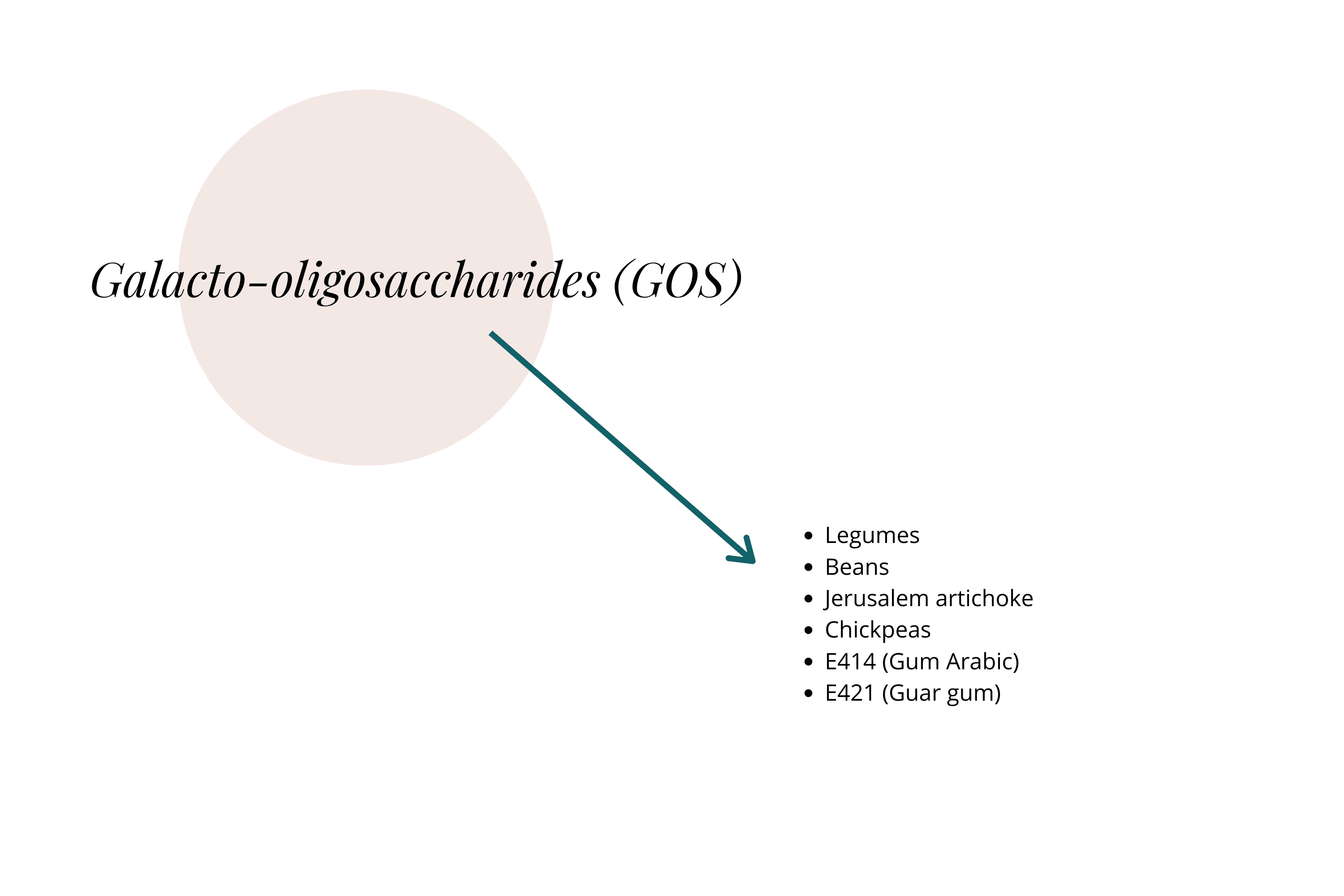

Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS): Legumes, beans, Jerusalem artichoke, chickpeas, gum arabic (E414), guar gum (E412).

Polyols: Sugar alcohols often found in artificial sweeteners—mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, etc.

Lactose: The disaccharide found in milk products.

Many foods sit in both prebiotic and FODMAP categories. This is why working with an experienced health practitioner who examines your personal gut microbiome is valuable—they can determine which foods, supplements, and bacteria you need more (or less) of.

This is especially true if you have known IBS concerns—prebiotics may actually worsen symptoms without addressing underlying gut lining damage and dysbiosis first.

Ready for a Targeted Approach?

Prebiotic foods are a beneficial addition to most diets—not only are they full of fibre, but prebiotic wholefoods come conveniently pre-packaged with complementary nutrients and minerals. They promote gut health by increasing beneficial microbes like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria and providing a cascade of SCFAs.

However, if you have chronic digestive issues, histamine intolerance, or symptoms that worsen with high-fibre foods, a more targeted approach is needed. Testing your microbiome first reveals which bacteria you're low in, which prebiotics will feed them, and whether underlying imbalances need addressing before increasing prebiotic intake.

At Prana Thrive, we use comprehensive metagenomic testing to identify exactly what's happening in your gut. Every test is reviewed by Amanda (who has personally analysed over 2,000 individual microbiome tests) with scientific oversight from Victoria, our in-house microbiologist.

Our AIM Method™ (Analyse → Integrate → Monitor) ensures:

Analyse: Comprehensive testing reveals your bacterial populations, identifying which prebiotics will benefit your specific microbiome

Integrate: A personalised protocol incorporating the right prebiotics (and avoiding problematic ones) alongside dietary and lifestyle modifications

Monitor: Follow-up testing and consultations to track changes and adjust your approach as your microbiome evolves

Book a free 15-minute evaluation call to discuss your symptoms and find out if testing-guided prebiotic recommendations are right for you.

We work with a limited number of clients each month to ensure everyone receives the attention they deserve. If you're ready to stop guessing which prebiotics might help—and start knowing—book your call now.

Book Your Free Evaluation Call

Related Articles:

Service Pages: